I will now go back and take up some events in my early life which changed all our lives. Mother went to church on Thanksgiving in 1887 and took sick that night. There was no doctor near, nor telephone, so a man went to Harrisville and got Dr. Hall. He said it was typhoid fever. With all the care we could give her, she only lived a week. We sent a telegram to Virgil, who was in New York. It was delayed, so he got to the church after the sermon was partly over. He stayed a week, and Father went back with him and stayed for a short time. This was the only time Virgil has been in West Virginia since he went to New York in 1882.

Cleo and Emza kept house for nearly a year. Then Emza got married, and Cleo did the work herself. This was very hard as we would have eight or ten hands in harvest. She would get up at 4 a.m., get breakfast, prepare dinner, and fix supper and take it a half mile on the hill to the hands for a five o’clock supper. Hands began at sunrise and worked till sunset then. Cleo had never been very strong, so this was too hard for her; but she never complained. In the fall of 1889 Cleo went to school in Salem, and Aunt Delilah (Father’s sister) stayed with us. Then the next year Cleo went to Alva’s at Alfred and never stayed with us any more.

We kept bach, but Father was very restless and was away a lot, leaving Delvia and me to care for ourselves-which we both enjoyed. In the spring of 1891 Father went up to Alfred to get married. He stayed for about two months. We kept house, did the work, and put in the crop. Someone told Father that Ellsworth said he had lost $500 by being gone. He never said any such a thing, he told Father when he asked about it; for he thought we got along better while Father was gone than we all three did when he was there. I doubt if Father liked that very well.

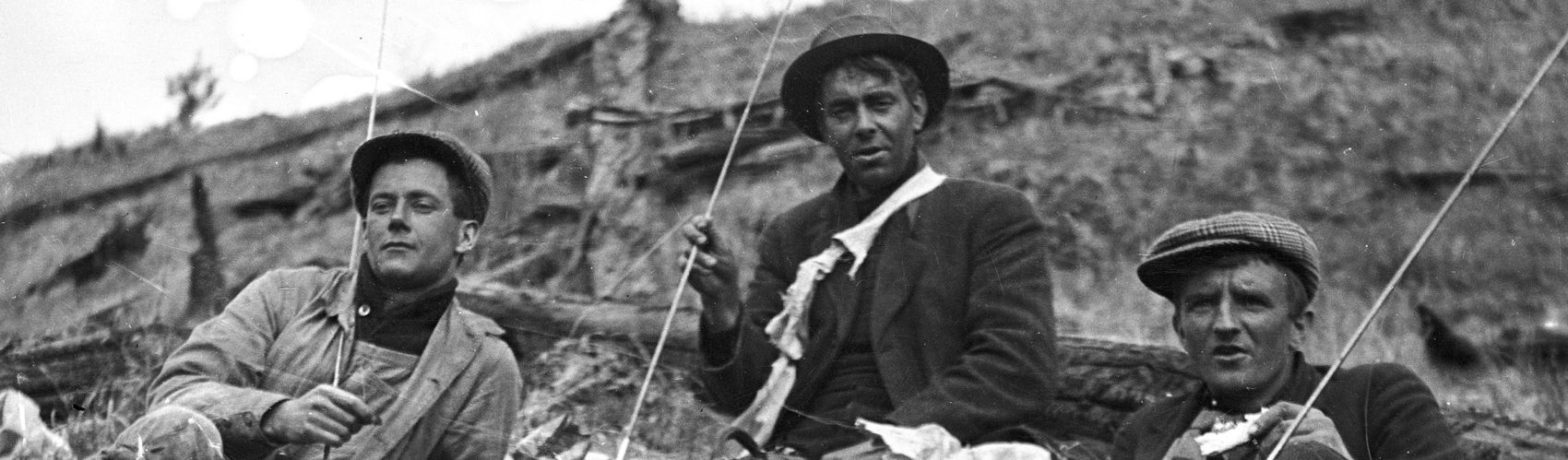

Gigging: It was while Father was gone that we asked Elva and Dow down to go gigging with us one night, as we found gigging was quite good that spring and there was no fishing on the head of Otter Slide. We split up poplar rails into small long pieces, which we tied into long fagots. We tied these up with leather bark (the bark of a small bush which peels well early in the spring, and is quite tough). These fagots are from 6 to 8 feet long, make a fine light, and burn for a considerable time. We started out as soon as it was dark. We soon found there were fish on the riffles. I carried the torch, and Elva carried the fish in a sack pouch over his shoulder. At first I had the heaviest load; but by the time we got to the bridge, the sack was heavy. In some places we saw ten fish for every one we got, but we got plenty.

Just as we got under the bridge Elva exclaimed, ”Look there.” I did, and there was a bass! It looked as if its back was out of the water although the water was over a foot deep. I told Elva to hold the torch, for I feared he would fail to get it as he had never gigged before and a bass is hard to hold. I hit that bass as if I meant to kill a bear. I hit it at the gills, and it was so deep through that it turned on its side and cut its spinal cord; and it never flopped. It was over 18 inches long. Oh, it was a dandy! When we got home, we had about a bushel of fish. Elva and Dow surely did have a great time, and I was so glad for they were the best friends we had for many years.

How I wish that Elva, Dow, Delvia and I could be together to fish, hunt and roam around over our old playgrounds! But alas, Dow is gone; Elva is not able to do anything; I am a wreck; and Delvia is far away. So we can never all meet here again. But I hope we may meet again in the future when the troubles of this life are over.

Father Returns with New Wife, Then Moves to New York: When Father was to come home, Ellsworth and Sarah went after them in the road wagon. They had to go to Pennsboro (14 miles), where they left the train. As we had a sheep to shear at John’s, we went over there to shear it in the afternoon. Just as we got back, Ellsworth drove up with the folks. Father said we would have been more presentable if we had been dressed up, but we told him we had been shearing sheep. That evening he told me I would have been more presentable if I had on collar and cuffs. Now I had asked Father to get me them before he left, and he said he never had anything of that kind when he was a boy. On Sabbath he said the same thing again, and I told him what had been said in the spring.

Delvia and I did not get along extra well with Mother Randolph, but both sides were to blame. But we never had any real trouble.

That fall I was 19 and taught my first school at Lower Otter Slide. I expected to hate teaching, but I enjoyed it so much that I decided to make it my life work.

That winter a letter came to Mother Randolph from her sister that she was very sick (she was a dope fiend) and wanted her to come at once. She went and did not return, so Father went and took Delvia with him in the spring of 1892. He offered to send me to school until I could get a first grade certificate if I would go with him. I did not go for several reasons. I got a First Grade that fall, so it would not have helped me much. I did not like Alfred, and still don’t. I had become interested in a girl (not girls), so I stayed in West Virginia. Had I gone, my whole life would have been changed and that of my family. I still am glad I did not go; knowing my disposition, I would never have been happy there.

Some Changes I Have Seen

I will now tell you of some of the changes that I can remember. The first buggy was owned by Jonathan Lowther. I was 8 or 10 years old when he got it. Mr. Brake got the second, which was the first with a top as the first one was a buckboard. Father got the third buggy. It had a top, and he sold it after Mother’s death. Mr. Brake bought the first mowing machine about 1884; Father bought one about 1887 or 1888. Father had a turnover rake made about 1885. This was about 8 feet long, so you could rake an 8-foot strip. It was pulled by a horse while you walked behind and tripped it whenever you wanted to make a windrow.

In 1892 I had never seen an auto, an airplane, a radio (in fact, none of these existed at this time), a reaper and binder nor a telephone. I had never ridden on a train nor seen a streetcar, had never heard of a refrigerator, nor seen a washing machine. We had no solid roads; for about four months out of the year the mud was so deep that a wagon could hardly get through. There were no electric lights in our section (we made candles sometimes), and all heating was done with coal or wood stoves. We knew nothing about electric milkers, bathroom fixtures, nor sweepers. Oh, things were different then! What would we do now without typewriters, adding machines, and so many other inventions that we never stop to think of?

Much to Be Thankful For

I will say right here that life has been good to me. I have had many good friends; my wife and I have lived together for over 55 years; our children have been good to us; we have enough to live on fairly well. Yes, and we still have fairly good health-so what more can we ask?