Ashby’s Memories — Teaching Again at Jarvisville

I taught in Jarvisville eight years, and my pupils were considered excellent in junior high and high school at Bristol in both scholastics and athletics. Jarvisville won so many scholastic ribbons at the Field Meets that they quit publishing the results and then quit the contests. My 4-H Club was great, as was my Boy Scout Troop. We had wonderful times at Camp Mohonagan and other places.

Ball Teams at Jarvisville.

I had one, among many, special school-softball games. The coach of West Milford High School brought the sixth grade softball team over. They were fine-looking boys. I had to have fourth and fifth graders and even three girls on our team. We played across the schoolyard fence in Bill Jarvis’ meadow. (Mr. Jarvis always let us play there.) Mr. West, the coach, insisted that he umpire because it was difficult for me to get through the fence. Mr. West umpired from behind the pitcher and coached his pitcher but didn’t help mine. I was sure he missed calls at home plate in his favor. Some of them I didn’t even think were close. Even after all that, we beat them 10 to 9.

I had the presidency of the men’s softball league, and I had a lot of success with a women’s softball team. We were blessed with outstanding athletic families: Myers, Stutlers, Jarvises, Posts, and Westfalls. In different end-of-the-season Jackson’s Mill Roundups, we won in girls’ softball and men’s volleyball. One special time during the second World War, we had such a hard time getting a team; but we won two 1-0 games of men’s softball in one day.

Teaching at Laurel Run

In the year 1947-1948, I went to the Laurel Run one-room school. You might be interested in hearing how I came to be moved. I did not ask to be moved. There had been a small group watching for me to make a mistake from the time I first went to Jarvisville. (I’ve heard that if you don’t have opposition, you are not doing anything.) Once the buildings superintendent came stomping into my room during a class. (He didn’t even knock.) He said, “Get the front door open.” I said, “Let’s go outside and talk.”

He went outside, and I explained that we had our kitchen in the primary room where it disturbed the classes and that the P.T.A. had put it in our hall. He saw the need of a kitchen and promised to build one, which he did while we used the one in the hall. That really cooked the opposition.

The last straw that made the county superintendent move me occurred when I wouldn’t promote a boy into my room. His mother was the daughter of an important doctor in Clarksburg. He and the superintendent were members of the same club. So I was moved and the boy was transferred to Bristol Grade School.

That move was one of the best things that ever happened to me. The day school started, the principal of Bristol Grade School came and asked me to teach all his arithmetic classes and nothing else if I would get my one-room school to go with me. I didn’t accept or even mention it to the parents, although that was the job I had always wanted.

My twelve years at Laurel Run were full to overflowing with pleasure and successes. The parents and community were enthusiastically behind and with me. We had a 4-H Club, a Boy Scout Troop, a wonderful hot lunch program and a great P.T.A. Our sixth-grade graduates did great in their adult lives.

4-H Clubs.

Usually all of my eligible pupils belonged to the 4-H Club. The girls usually took the same projects–like cooking, sewing, or craft. The boys took woodworking, gardening, and birds, mostly. They won lots of first-, second-, and third-place ribbons, which made them, me, and the community very proud. I remember one year when a lot of them had bird projects. We had a bird feeder against a window, and the birds became very friendly. The boys took pictures of many kinds of birds eating and put them in their project circulars. I remember once my girls in the craft class made each of their mothers a Tom Thumb change purse of leather, and the boys made their daddies each a key case.

Boy Scouts.

Our Boy Scout Troop was equally successful. My son, Ashby Bond, was their scout master after I decided they needed more hill climbing than I could give them. Later a great community man, Cecil Fultz, was scout master. I was always on the Executive Board and often took them to camps like Mohonagan. These scouts made real successful men. One is a high school principal in Cleveland, Ohio. Another is high school coach in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. Another has traveled all over the world (some of the time in a submarine). He was a communications officer, having charge of building an observatory in Alaska and retiring from the Naval Observatory in West Virginia. One of my 4-H girls graduated from Salem College Cum Laude and is in charge of a library in Detroit, Michigan. I am extra proud of this girl because I started her as a wee-tiny first grader and had her through the sixth grade.

Hot lunch program.

Our hot lunch program was a success mostly because the proof is in the eating and my wife, Ruth, cooked it the very best. The community (through their P.T.A.) furnished all the utensils we needed. I made the menus, using all the government-furnished food we could get. This use of free food let me charge 10 cents per pupil for the first child in each family; for each child after the first in each family, the charge was 5 cents. Besides, some families ate free because of their financial status.

I must tell you how I got all my pupils to like at least fairly well everything Ruth fixed. The children watched Ruth fill their trays. They got at least a tablespoon of each thing on the menu. If they thought they might not like a food, they only took a small tablespoon of it. When their trays were cleaned, they could get more of anything, as long as there was any left. I never allowed discussions about not liking any food, and it was amazing how many pupils learned to love foods they never liked before.

I used two special awards for cleaning the trays. Children who had their trays clean could go play after 20 minutes from the time we started to eat. All who could not clean their trays had to wait 10 more minutes. If all of the pupils cleaned their trays, we celebrated with a ciphering match or some other loved activity, like map-match, etc. We had to celebrate often, and a teacup would almost always hold the leftover food. Parents often asked Ruth for her recipes, and now and then a former pupil calls or comes to ask her for some recipe.

Special community affairs.

We had many community gatherings. At most of the holidays, we would have programs and a covered-dish meal. One of the special holidays was Easter, when the community would come in. Some of the patrons (led by a grandpa of one of my boy pupils, Ora Stutler) would hide eggs and candy for an egg hunt. They had a definite area of about an acre for preschool children only. We had regular P.T.A. meetings and special 4-H and Scout celebrations. It was an awful thing to give up all these community ties when they consolidated our school at Salem and sent me to West Milford.

Teaching at West Milford

I was hired to teach the fourth grade; but when I got there, they gave me a fourth and fifth grade combination. In those days, the Board did not seem to consider the teacher’s needs at all. I soon learned to like my pupils, their parents, and my principal (Mr. Laughlin). I especially loved my location and building. The building had been a two-story home, and it sat on top of a knoll separated from the main high school and grade building. We even had a private yard and the football field for a playground. In the upper story, a close friend of mine (Kester Fiddler) taught high school science. He told me when I first went there that if I needed anything to just let him know.

The second year they let me keep the same pupils as fifth and sixth graders. My parents asked for that, which made me very proud. I also talked my principal into letting us have a softball and volleyball league with each fourth, fifth, and sixth grade belonging. Every other teacher was a lady, and some didn’t like the league idea, but their pupils loved it. We did that two years; then the Board hired Mr. McLaughlin to be the high school superintendent.

This move of Principal McLaughlin (who had furnished my room with the teaching aids I needed and supported me in every other way) was a terrible loss to me. Mr. Hess, my new principal, would not allow me to use any extra texts. (He also stopped our inter-grade athletic contests.) The trouble was that I would have pupils who needed first-, second-, and third-grade texts in order to be able to read in them and learn from them. Of course, I made do with what supplementary texts I could find, but it would have been better with the principal’s cooperation.

The second year that Mr. Hess was principal (which was iiy fifth year at West Milford) I had to move out of the hilltop house because they were tearing it down to build a new school building. I also got only fourth-grade pupils, which meant I got all new pupils each year. This meant I had to teach all of them to prepare lessons at study time and keep order so all could do their thing. This took paddlings or other punishment for the first month or so.

It was not all trouble. We had a basement room with an empty room adjoining that we used in bad weather for games such as dancing and relay games. We also had the high school gym (because they had been moved to a new building) one period a day for recreation. This gym was a great place for singing games, leap frog, some gymnastics (especially tumbling), basketball drills, and some calisthenics each day. The other teachers had a high school pupil give their class calisthenics at their period in the gym. I always thought a child got better exercise from games and that they learned from them too.

This effort of mine to give my pupils clean supervised play (instead of their running over others or being run over or forming gangs to run over those they couldn’t run over by themselves), alone with my having the principal’s only child in my room, caused my principal to come stomping into my room at opening exercise time one morning about one month before the end of my last year of school teaching. I tried to greet him friend-like, but he went to ranting and throwing his arms through the air, accusing me of not teaching anything but ball for the last two months. When I tried to get him to listen to the pupils’ ideas of what I had taught, he would not let them talk. Instead he just stomped out.

I had to teach all day while I was the maddest I think I ever was in my life. As soon as school was out, I went to the superintendent’s office to get a hearing on Mr. Hess’s accusation. They (the superintendent and the grade school supervisor) explained at great lenpth that my principal would apologize. He did apologize, and my pupils’ parents gave me a tackle box full of baits at our Last-School-Day Picnic. Also, my principal and my co-teachers gave me a fine folding chair as a going-away present. I retired at the end of the school year in May, 1966.

Ruth’s Memories — Community Spirit

There was a lot of “Community Spirit” in those days. Ashby organized a men’s softball league (usually six or eight different communities). Each team usually had one home game and one away each week (on Sunday afternoon and one week-day evening). All the communities were well supported.

About every Sunday morning during ball season, some of the local fans gathered here with stuff to make ice cream and lemonade to sell at the ball game in the afternoon. That is how they got money to buy equipment. Some communities were lucky enough to find some business to sponsor them and furnish what they needed.

They still have softball leagues, but they are on such a large scale that there is nothings personal about them. The big thrill is gone.

The same thing happened to our one-room schools. When the school was closed and the children were sent farther away, a bit of the heart of each community was crushed. There were four schools on Turtle Tree Fork of Ten Mile Creek when we first moved here, and in 1960 there were none.

Summer of 1945

In May 1945, Bond was called to serve his country. He was sent to Camp Hood in Texas. Brother Ian had been called to service as a medical doctor. He was near Lake Dallas–also in Texas.

Xenia Lee and Edgar were married in August of that year. Since it was wartime, the gasoline was rationed. Ed tried to get gasoline to drive to his home in Kansas, but could not. So he left his car here, and they went by train. They had been at his home only a short time when the war was over and the ration was lifted. They wrote that if we would bring the car to them, they would take us to Texas to see Bond and Uncle Ian.

Since Ashby was a school teacher, there was little income in the summer. A good neighbor, Vivian Post, lived just down the road from us. (We quilted quilts together in the winter time, and she visited us often in the summer.) She was here when the letter cane from Ed and Xenia Lee. I said, jokingly, “If you will loan us $100, we will take the car to them.” She said, “If you will take me to the bank, I will get it for you.” I was really shocked, as I was just kidding. She insisted, so we decided to go. We were on our way by afternoon!

Ashby was afraid the car might break down, so he would not let me drive over 45 miles per hour. We made it with no problems. They were ready to go, so with little delay we were on our way to Texas.

We located the hospital where Ian worked. He wanted to show us around some before taking us to his home. It really was hot and dry. Ashby thought he would wait for us in the car. By the time we got back, he really had a sick headache. Ian’s home was on a lake with lots of trees around, so Ashby soon recovered. Bond arrived the next day. It was so good to see him again.

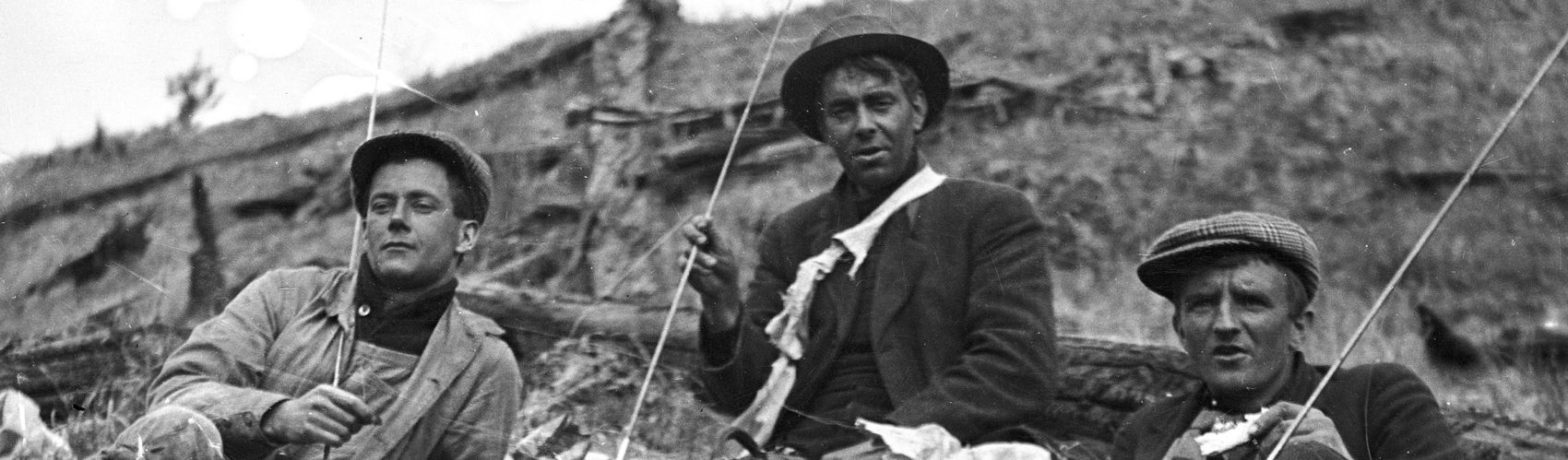

We went fishing in a small boat on the lake. We did not need poles. We would bait the hooks and let the line down in the water by the boat, then wrap the other end around a finger. Sometimes we would feel a little quiver and pull up the line. We caught a few fish–but none to brag about. It was fun, anyway.

The next day we took Bond back to camp and started on our way back home. We took the southern route and stopped in Cleveland, Tennessee, to see Avis and family. We made better time coming home (only had tire trouble once, and that close to a filling station).

It was good to be back home. The tomatoes had just started ripening when we left; and when we got back, the children had canned over one hundred quarts. They proved they could “keep house.”

Car Accident in.December, 1945

Bond got home on “Leave” before Christmas that year. It was real winter, and the roads were icy. Alois, Mae, and I started to Clarksburg to meet him about nine o’clock at night. Before we got there, the tire chain got broken and wrapped around the axle. We had to stop, and Alois went to work getting the chain loose. He was almost finished when a car going east met a car going west. That blinded the driver, and he did not see our car–so he ran into the back of our car, running over Alois. Other cars were soon there; and before I knew it, someone had Alois in his car to take him to the hospital. Mae went with him, and I stayed with the car, waiting for the State Police. I guess they were busy elsewhere, because they did not come. After a while Lyle Dennison came along and took me to the hospital. We had Bond paged at the train stop to tell him to come to the hospital. Lyle took Bond and Mae home, and I stayed with Alois. X-rays showed a broken pelvis and also broken loose from the spine.

Bond went to Weston to see Ruby the next day. They decided to get married on Christmas Eve. After close to a year in Germany, Bond returned home in time for Christmas the next year.

Alois recovered in due time and later served a time in Korea.

Lydia’s Illness

In 1956 while Ashby was teaching at Laurel Run, Aunt Lydia was having her last bout with cancer. Aunt Susie took care of her and Aunt Ada did the house work. As soon as I could get lunch over and dishes washed at school, I went to Salem and took care of Aunt Lydia while Aunt Susie went to bed. After Aunt Ada finished her evening work, she took care of Aunt Lydia until Aunt Susie got up; I came home. Ashby rode the school bus home. Beth got supper. Edna Ruth was staying here at the last expecting Tim any time. She often went with me so I did not have to drive home alone. Aunt Lydia often said, “It’s a good thing there were four of us girls–one to be sick and three to care for her.” We were glad we could care for her at home.

More Neighbors, and Deer Hunting

Ray and Anna Lou Shay were close neighbors for a time. He loved softball and hunting. His home was at Newburg (a good place for deer). That deer season Ashby got someone to teach for him, and we went to Newburg with Ray and Anna Lou.

At the time the ground was bare, but it was cold. That night snow came, and by morning there was close to a foot of snow. That just suited the hunters, but it was not so good for Ashby on crutches. We were able to drive near to a good “stand.” It was really cold, so someone got a fire started. There was lots of firewood around, but it had to be cut up. That became my job–to cut wood and keep the fire going. They would come in to get warm, then go on another drive. They had some excitement a few times, and the guns roared–but no one got a deer. No deer came in sight of us (Ashby thought it might be because of the fire). We had a good time, anyway!

After that, when it was real cold, we learned to heat bricks and wrap them up well for Ashby to put his foot on. Then we wrapped blankets around him and his chair, leaving room to get his hands out. We put a card table in front of him for his gun and ammunition.

Ashby did get one deer finally. He has not been deer hunting for a long time. The weather is not right for us any more.

Ashby as an Outdoorsman

Ashby was always a lover of the big outdoors. He never stayed in the house when he could be out in the fields or woods. He knew the trees by the shape of their leaves and by their bark. Many he recognized as far away as he could see. He knew the birds he saw, and many he recognized by their song or tone of voice.

Ashby also loved to hunt. He was satisfied with just enough for one meal. It was a big blow when he could not get out alone. I made up for it as much as I could. I just fit under his left arm, and I used his crutch to help keep my balance. Many times I helped him up the hill into the woods to watch for squirrels. At first I went back to the house to work, but I found that was not good. He would shoot a squirrel or two;, and by the time I got back, I could not find them in the leaves. He did not get to go as often as he would like; but when he did, I stayed with him and.enjoyed “the great outdoors” too.

After Ashby got his “Wheel Horse” and cart, I loaded his supplies in the cart and he drove his tractor around the road back on the hill while I walked. He drove the tractor as close as he could to good hunting, and I helped him the rest of the way. I had many pleasant hours in the woods, too. Maybe that has helped to keep us healthy. Anyway, this has been a good life.

Since we had the pond made in 1963, Ashby has had a good place to fish while he enjoys the wildlife that comes around to keep him company.

Some of My Activities When Ashby Taught at West Milford

It was a great day when Ashby was transferred to West Milford. It is only a mile from Aunt Susie’s. I usually went with him and then went on to Aunt Susie’s. Aunt Ada was living with her. Part of the time Aunt Susie was working caring for the sick in their home. I helped with whatever needed to be done.

When we could, I took Aunt Ada to see old friends around home near Roanoke, a cousin on Indian Fork, friends in Weston, and old friends of Aunt Ada’s around Lost Greek. (She had kept house for Uncle Orson back in 1916 and 1917 when he managed the Van Horn Farm three miles from Lost Greek.) (By the way, that was the farm where my grandmother was born and reared.) It was great fun for me to hear their tales. They enjoyed old memories very much. When Aunt Susie was at home, she went with us. I was always back by the time Ashby was ready to leave school.

When Aunt Ada heard Ashby was retiring, she said, “Shoot! I’ll never get to go any place again.” She was about right.

Combined Memories of Farm Products — Regular Farm Products

In the 1930’s Papa and Mama Bond began selling whole milk. They had been separating the milk and selling cream. They gave us the hand machine that separated the cream from the milk. We had three cows and got the fourth one. That made us a little income to help with expenses, and the skim milk raised good pigs to help with the meat supply. We kept a few chickens and butchered a beef every year. We always raised a garden and canned lots of food.

Maple Syrup

One spring we decided to make use of the maple trees around the house. Ashby found some sumac an inch or so through and cut them in one-foot lengths. About four inches from one end, he would saw half way through, then split it off. He cleaned the pith out where it was split and punched the rest out. He rounded the end to fit the size of the auger he used to bore a hole two or three inches deep in the tree. The spile was put in the hole and tamped to fit tight so the sap would have to flow through the spile. Three or more spiles were put in each tree, depending on its size. A bucket was placed under each spile. Some trees had sweeter sap than others–also more of it. As much as two and a half gallon bucket might be filled in eight hours or so. We had free gas, so I boiled it down in a five gallon pot on the kitchen stove. After it started to boil, I heated sap in a gallon pot to fill in so it never stopped boiling. It took ten to twelve gallons of sap to make a quart of syrup. One had to watch closely when it was nearing the end or it would boil over. Sound like work? Not really. The maple syrup was worth it.

Sassafras Tea

Another thing we used to do in February was to dig sassafras roots to make tea. The small roots were cut in small pieces. On the larger roots, we peeled off the bark. Some of that cooked in maple sap needed no other sweetening.

Cane Molasses

Another thing we used to grow was cane to make molasses. Now, that was almost work. The seeds were tiny, and some did not grow so one planted several seeds in a hill two feet apart. Then it had to be thinned to leave three stalks to a hill. Of course, it had to be cultivated. Just before frost the blades had to be stripped and the seed stem cut off. Then the stalks were cut near the ground to save all the sap possible. The cane heads were fed to the chickens.

After the cane was stripped of seeds and blades, it had to be hauled to the squeezing mill. This mill had two heavy steel rollers fastened to a long pole which turned the rollers so they sucked or guided two or three stalks between them to squeeze the juice out and into a tub. It was a job that kept one person busy feeding that mill. Mostly we fastened a horse to the long pole so that it went round and round pulling the pole. Once we let Alois drive a car to pull the pole that made the rollers turn and squeeze the cane. That was the beginning of Alois’ driving, which he has done a lot of.

(I almost left the cane juice in that tub; but I was afraid you might taste that juice, which would be quite bitter.) The making of molasses took a lot more work. Wood had to be gathered and an oven built for a pan (or an evaporator) to boil the sap down in. While it was boiling, it had to be skimmed off with a paddle as fast as the thick scum formed. Then a special person with skill and experience (Ruth) had to keep testing the boiling mass to determine when it was good molasses so it could be put in half-gallon glass jars. The proof of the molasses tastiness was in mashing a lump of butter (about a tablespoon heaping full) into two tablespoons of molasses and spreading it over a hot pancake and eating it.

During all the boiling, a skilled fire-keeper had to feed the fire just at the right place and the correct amount to keep the sap boiling without foaming over the sides. This was done by feeding the new wood to the edges of the fire, keeping the fire in the middle. Susie’s family usually grew cane when we did, so we worked together in making molasses. Our boys hated that job, so we quit growing cane. We did not quit working together when either had a big job to do.

Blackberrying

Blackberries were plentiful then, and we tried to can at least 100 quarts–and some juice for jelly. (Now, around here anyway, the blackberries have a kind of blight that keeps them from maturing.) When berries were plentiful, we used to pick several gallons and sell at $1 per gallon. That helped when money was scarce in the summer time.

Strawberries at Susie’s

After Everett passed away and Lee and Charles were working away from home, we used to go to Susie’s and help out when she had a big job to do. Then they would help us out when we needed it. One year they had a big patch of strawberries. Every two days the berries had to be picked. Ashby saw that no dirt or bad berries were among them as he put them in baskets ready for market. The damaged ones we made use of.

Huckleberries

One summer a neighbor said that if we would pick six gallons of wild huckleberries for him we could have the rest of the crop. We picked the six gallons so quickly and the patch was so big that Susie’s came to help us. It took two or three days to pick the ripe ones, and then in a few days we had to pick them again. One could set a bucket under a branch and almost shake the ripe ones off. That made them hard to clean. Ashby worked at that until we got them picked; then we all helped. We sold a lot of gallons at $1 per gallon, besides all we canned for ourselves. We kept account of the gallons we picked until it passed the 100-gallon mark. We picked some to eat after that.

Apples and Applebutter

One fall when Grandpa Randolph had a bumper crop of apples, we got a truckload. Besides both families canning applesauce, we made over forty gallons of applebutter. We got the apples ready to cook the day before. We had a 24-gallon kettle with a frame for it to set in about a foot from the ground. We would fill the kettle 3/4 full of cut apples, add 1/2 gallon of vinegar and enough water to come half way up on the apples. We liked to use dead apple wood when we could get it for that burned well and made a hot fire. We put some silver coins in the bottom of the kettle for that helped keep the apples from sticking to the bottom. We cut the wood in short strips so it would not burn up on the sides of the kettle. Then we kept adding new wood from the side so the hot coals kept it cooking all the time. As soon as the apples started cooking, we began to stir them with a long-handled paddle that was solidly secured, something like this illustration.

One stirred all around the side of the kettle, then back and forth across the middle, constantly, to keep the apples from sticking. As they cooked down, more cut apples were added until the kettle was about 3/4 full. Then sugar was added, three pounds for each gallon of applebutter. We kept stirring until a spoon of applebutter in a flat dish left a mark when one ran the tip of a spoon through it. Then the fire had to be removed, oil of cinnamon added and well stirred again, the jars filled and sealed. That sound like a hard job? We loved it. We tried to find a shady place to sit and stir.

One time a neighbor, Bytha Davis, went with me up to Grandpa Randolph’s when Grandma was there. We got there before noon. Grandma had enough apples ready to put on to cook for applebutter. We made that in the afternoon. Then we got apples ready that evening to make another kettle of butter the next morning. We came home in the afternoon. She often told me she never worked so hard in her life. I told her that was just an average day for me.