The covered bridge over the Hughes River was the meeting place for the children of the little Ritchie County community of Berea, West Virginia. The boys must always show their prowess by walking all the way over the founded beams that supported the side of the roof of the bridge. When they had successfully maneuvered their way across (it was very seldom for any one of them to fall the fifteen feet to the floor of the bridge, and when they did, Old Doc quickly splintered their broken arm), it was time for the girls to try their skill. They were never permitted (by their brothers),to go more than a third of the way up, and then they could sit quietly there to rest on their laurels before backing down to the safety of the bridge floor.

There was an open gas flame on a pole between the village store and post office. Since this was the only outside light in the community, it was the gathering place on summer evenings for the children. Fireflies, moths, and all other flying insects also considered this the proper place to spend, and I do mean spend, a worthwhile hour or two.

As the children played, the men discussed the events of importance. Politics always came in for its fair share of argument. Teddy Roosevelt and his exploits were either the greatest or the world’s worst, depending upon which “Party” you supported. News of the outside world would arrive by way of the mailman about twice a week, but in between times the “old news” would suffice for heated discussions.

The mothers of the community rarely entered into village play and deliberations. There were always stockings to be darned, trousers to patch, and a million-and-one other things to occupy their time. They baked their own bread for the family, washed their clothes on a scrub board and ironed them with a “flat iron.” They dried and sulphured their fruit and vegetables that would suffice for food during the winter months. (Not many things could be canned in the early twentieth century. Pork was preserved by salting and beef by drying.) Fodder beans (dried beans in the pods) was a staple food for winter meals, and I still like them. The women also made all the clothes for the family with the exception of a “Sunday suit” for Dad and the boys after they “grew up.”

There were a few days of the year when the women folk could really shine. Among these special occasions would be: First, there was the thirtieth day of May picnic when buggies and wagons would come to Pine Grove from as far as five miles away. (I must tell you a little later how ice cream was provided for this feast.)

Second, the community Christmas tree at the school house. There would be a program using all the local talent. The tree was lighted with candles that glowed with a far greater splendor than any of the modern day lights. The gifts had no fancy wrappings, but were just hung from every branch and piled on the floor under the tree if they would not hang. After the program in the school house, fireworks were put off from the hill overlooking the village. There might be a half-dozen “Roman candles,” dozens of “sparklers” and firecrackers without number.

Third, there were bean stringings, apple cuttings, and quiltings which were days for social gatherings in which the women would really show their skills. Perhaps five to ten bushels of beans would be picked and the neighbors would come in to help prepare them. There would be music and games for the young folks and work and talk for the others. The next day these beans would be washed and partially cooked and placed into a large barrel and left to sour. After about three weeks, they would turn into delicious “pickled beans,” and would be eaten every day during the long winter months. (If you don’t think they would be good, get a recipe and make a gallon of them. Your family will enjoy the change.)

Another big barrel was used to sulfur apples. If you have smelled sulfur, you will wonder how anything could be eaten that had been around that terrible odor. When the proper amount of sulfur was used, the apples remained white and had a fresh taste when cooked. Bushels of apples were dried. You can still buy dried fruit in stores, peaches, apricots, prunes, and even apples, but they turned very dark and had a different taste when cooked.

Nearly every home in the community would have a quilting day during the winter. The women folks would piece quilts all year and finally when four or five were ready to set in the frames, the neighbors would be invited in to help quilt them. It was important for the young ladies to learn to be good quilters if they wanted to be recommended to the most eligible young men. All day long the sewing and laughing and talking continued. When evening came, this family had new quilts to keep them warm.

I guess there may be one or more strange characters in your area–there was, and is, in ours. Poor Toody lived in anticipation of these special days and she never missed one. She wasn’t much good with the needle, but she was “S-1” at the table. She would manage to get to the “first” table and remain through the second and third shifts. When everyone else had finished, Toody would finally leave the table weeping and when asked why she wept, she would say, “It is so sad that I can’t eat more when there are such good things left.”

The farmers assisted each other at wood cuttings, corn huskings, and hay harvesting. These were family gatherings because the women came with food and brought the children along. The boys and girls were responsible to draw water from the dug well and keep the men in the field supplied with fresh drinking water. The best food available was provided on these occasions, even pie and cake.

Let me tell you how a group of people who work together can provide special treats for themselves. In our locality there was an old one-room log house. This house was filled with sawdust. When the river froze over solidly, the men would go down and cut out chunks of ice and store them in the sawdust. Each participating family would be permitted to remove a certain number of blocks for his own use. On the 30th of May, ice cream would be made for all the picnickers. Sometimes there was enough ice left to have ice cream for the 4th of July also!

The three-room school house in the heart of the village served the countryside for miles around. The pupils varied in age from 5 to 20 years and the teachers were sometimes younger than some of their charges. I was lucky, though, for Dad was my first teacher. We lived in sight of the school and I was permitted to go in the fall before I became five. I recall asking to be “excused” and then running home to get a “piece.” One day I whispered and disturbed Dad and he punished me by placing me on the corner of his desk with a “fascinator” tied around my face so I couldn’t see. (A fascinator was a head scarf made of a long narrow piece of woolen cloth.) It was a serious punishment for me to have to sit quietly and have no one with whom I could whisper.

The village store was a treasure house to the youngsters. They always had candy: rock candy that looked and tasted about like a rock, except that if you sucked carefully on it, you got a faint taste of sugar; maple sugar candy that was molded into exciting shapes–hearts, stars and cubes–and it was really good, even though it had been left in the open to dry out by the month so that it became as hard as the rock candy; several varieties of stick candy were always awaiting the one who had the nerve to try to bite them; green pickle candy was the real treat. It looked like a small pickle and was as sour as a homemade pickle. These precious tid-bits came pretty high–one egg carried carefully in the hand and presented to Mr. Jackson could be exchanges for two “pickles” and they could last all day if you gave yourself a little rest before you started on the second one.

Even a community of thirty-nine people had its characters. There were Uncle Jake and Old Doc, Aunt Perdillie and Aunt Lovie, these were their real names, who were the “salt of the earth.”

Uncle Jake liked children, I guess, and he was always after them about something. He walked with a cane. This cane had an especially big crook in the handle, and any child seeking to slip by Uncle Jake for any reason at all would find himself brought face to face with the old man by the force of that crook around his neck. Every child feared him, but no one ever heard of any harm done by him to anyone.

Old Doc had delivered all the babies in a fifteen-mile radius and watched them grow into men and women. He always made each child feel he was someone special. To every girl he would say, as he patted her head, “Pretty as a peach with the fuzz rubbed off.” To the boys he would say, “Oh, that muscle is really developing.” Any time a child had to be taken to his office, which was in a little white-washed shack in his front yard, there were some candy pills doled out into his hand, as many sometimes as a half dozen, and they were sure to do the trick, even if you were still sick a week later.

Aunt Perdillie and her husband, Uncle John, lived in a two-room house in the heart of town. He was paralyzed and unable to walk, so he sat all. day long in his rocking chair while Aunt Perdillie went out to do a few chores for neighbors to earn their living. They received an old-folks pension of $5.00 a month, so with the things given to them by neighbors, they got along. She would give a penny once in a while to a child who would sit with him at times when he was feeling “poorly.” She was highly respected for her devotion to her crippled husband. Children would sit by the hour in the shade of the house on a long hot afternoon, soaking up “local color.” There was no better way to her the news, for she was the town “gossip.”

Poor Aunt Lovie was renowned for her stinginess! When she had guests for a meal, she could be expected to say, “Help yourself to the butter. There’s more in the cellar in a teacup.” She was the guardian of her precious loaf of bread, for she kept it in her lap and if someone asked for a slice, she would cut it and pass it over with the remark, “I don’t like to cut any ahead, for it dries out so bad.” Her idiosyncrasies were always good for a laugh when the men gathered for a session.

Religion played an important part in the lives of these country people. There were two established churches, and when a third one, -Seventh Day Adventists, sought to establish a congregation, the holy ire of the community was aroused. The new minister was forced into public debate and thoroughly humiliated by the men of the community who tricked him into “deep water” out of which he was unable to swim. Their objections to this new doctrine did not concern the keeping of the Sabbath, for the majority of the community were Sabbath-keepers, but they objected to the ban on the eating of pork and the doctrine of “soul sleep.” To this day, the Seventh Day Baptist group still have a church and the Adventists are only mentioned in connection with reminiscences.

The yearly “protracted meeting” was held in the late fall when all crops were gathered in and the work was slack. From every direction you could see the lights converging on the “church in the dell.” Each family brought a lantern to see to walk by and to use in lighting the church. Time had been spent in every household some time during the day in filling the lantern with coal oil and (:leaning and polishing the globe so as to get the best possible light from it. Sometimes mischievous boys would turn the wick up on some lanterns to make them smoke so no light could penetrate the globe. They were considered the Is roughnecks,” and prayers were said for their souls. The meetings frequently continued for six weeks with much rejoicing and an “experience meeting” each night when the grownups got to testify about their personal lives. (The truth about this was that everyone there already knew so much about each one as he knew about himself–sometimes it agreed with his testimony, and sometimes not.)

This meeting afforded the main social opportunity of the year. The young men lined up at the door to ask the young ladies of their choice if they might “see them home.” The two or three-mile walk through the mud or snow–whichever it chanced to be–gave ample time for exciting conversations and spills and pick-ups which provided a little harmless physical contact, always in the close proximity of the rest of her family (and probably his). The old folks and children were preferred as chaperones and permitted to carry the lanterns while the courters walked behind in order to make the most of the lantern light, so they declared.

The grist mills was always good for a few hours of interesting perusal if nothing else developed. The mill pond, formed by the dam, was too deep for a playground, but at times it was possible to walk across the top of the dam a few times without being caught. That was as exciting as the visit of a stranger in the village, and almost as rare. The great mill wheel was always turning, for there was never a shortage of water in the river. The splash, splash of the water as it came off the wheel could carry a contemplative child into the land of dreams where all sorts of exciting things took place.

When the mill was running, it was an exciting place to be. The farmers brought their grists of corn and wheat and stacked them inside the great dusty room. A bag at a time would be opened and poured into the hopper. Then the real entertainment began as one could run from place to place watching the progress of the grain as it was turned into meal or flour. Eventually it poured out of a chute into a bag and was ready to be used for baking bread, cakes, cookies or pies. The miller, in his flour-covered clothes, always divided the finished product, keeping one bag out of four for his share as payment for having ground the grain. The little country stores for miles around would stock their supply of flour and meal from his “share” that was always piled high in the storage room.

Winter was a wonderful time in this remote section. Ice skating and sleigh riding were the natural recreational outlets for about two months of every year. Even school days did not prevent the youngsters from skating and sleighing, since the river was near enough on the one hand, and the “hill” was in easy distance the other direction. So the noon hour afforded ample time to enjoy whatever sport was best at the time. I doubt that the lunch pail got much attention those days, only something that could be consumed “on the run” was appreciated. Practically every child owned a pair of ice skates, store-bought, and a sled, home-made, and learned to use them before he entered school.

The grownups were more likely to use the “river” and the “hill” at night. They would build bonfires and make a real social occasion of it. Some of the families had sleds drawn by one or two horses, in which they transported their families to church and other necessary places. A good layer of hay was placed in the bed of the sleigh and everyone crawled in and covered with quilts and blankets against the cold winds that were generated by the fast movement of that plow horse that was doubling as a racer for this occasion.

Many important subjects came in for their share of discussion around the stove in the store, mill, or blacksmith shop. The weather was always good for an opener, whether it was hot or cold, wet or dry. “Crops” would always strike fire if certain farmers were present, who invariably had the “most corn to the acre,” the biggest “punkins,” and so forth.

One subject that had top rating for several weeks was “Halley’s Comet.” The story was widespread that when this comet approached the earth, it would swing around and its tail would touch the earth and set it on fire. It would be the end of the world. This was discussed pro and con by the hour while the appointed time for its appearance drew near. The children were spellbound as they listened to the tale–afraid to hear it, but too curious to run away and hide. There were nights of troubled sleep for the young fry who talked in whispers about what it would be like if all the world was afire. Would the river be a safe place to hide? (It was as much as fifteen feet deep in spots.) Or would it be better to find a deep cave to hide in while the fire burned? The night the comet was to be visible passed without incident, and there was an unconscious sighing of great relief when the population awoke as usual and found themselves still alive and everything normal.

There was no such thing as a daily newspaper in that farming area, but there were a few families who took weekly and monthly farm and family magazines. GRIT was a great favorite as an all-around weekly news and specialty paper. YOUTH COMPANION carried a serial story and other features of interest to the whole family. The day the companion came was a special one, for everyone hurried a little faster with the chores order to gather in the “sitting room” for the reading of the continued story. One member read aloud, so all could get the exciting details at the same time. Today’s theaters would do well to secure some of the reading talent that was developed in those evening sessions! The best reader was urged to do the honors, since a great deal of their pleasure depended upon the romantic atmosphere provided by the voice, accents, and speed of the reader. There were some homes where even the best reader left much to be desired, but if it happened to be the story of an Indian raid, a slow monotonous voice reading, “As I stared toward the window, there appeared two feathers moving upward , and then the hideously painted face of a savage came into full view.” would help to ease the pain of suspenseful anxiety.

By the way, have you ever experienced the feeling of contentment that “all’s well with the world” sense of satisfaction that accompanies group reading? Get a few compatible companions and try reading poetry, a new novel, a book on present-day trends in race relations, a book on prison life in a Communist country, and see if life doesn’t put on new interest and emphasis.

Music had an important place in the lives of these contented people. There were few instruments in the community–most of them pump organs. Some churches had organs, and a few homes were so blessed, but few people learned to play them. Perhaps as many as two women would be able to play the church hymns. There was one accordion in the community, but it had little in common with the present day instrument. It had twelve (?) notes and two bass notes. (I still have one that my mother used.) Singing came natural with these people. Nobody had a trained voice, but nearly all could “carry a tune,” and they enjoyed doing so. Certain people were considered leaders because they owned a pitch-pipe, which would give them the proper pitch for starting a song. This was used when no instrument was to be played.

After the first frost fell in the fall of the year, a new and interesting chapter of life began. The gathering of nuts was the children’s contribution to the winter supply of interesting food. There were chestnut, hickory nut, walnut, butternut, and hazelnut trees in abundance. (Now all the chestnut trees are dead from a blight, and only a few of the others have survived the years.)

The most frequent and enjoyable excursions were made to get chestnuts. Those trees were large and grew outward more than upward. Longfellow described it when he said:

Under the spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stood

Chestnuts grew in round shells, or envelopes, that were completely covered with prickly burs. When they were ripe, these burs fell to the ground and frequently burst open on impact to reveal four sections which contained one nut in each. These burs were fully lined with a soft substance which felt like velvet. At times, the nuts seemed so content with their soft pleasant home that they were reluctant to leave it. In that case, you took a stick to force them out while you held on to the bur with your foot–if you had shoes on.

The pleasure of gathering these nuts was almost eclipsed by the pure delight of eating them. They were good in so many different ways. On long winter evenings, chestnuts Would be placed in the coals in the open fireplace and heated until they would burst open. It took careful watching to eat a hot one without getting burned on the shell. If there was no fire for roasting them, they Would be boiled and the taste was quite delightfully different. Then, of course, they were available for stuffing the Christmas turkey or, more completely, the rooster.

It was great fun to gather the hard-shelled nuts: hickory, walnut, butternut, and so on, but they were tiresome to crack and pick out.

Long hours of confining work were required to get a dish full of those nuts prepared for use in baking or candy making. They had very thick shells, and it took a hard lick with a hammer to crack one. (The shells are much like the shell of a Brazil nut, only thicker and tougher.) You had to hold the nut between your fingers on a piece of iron or stone and then whack it. Many fingers have been badly bruised in the effort, and thumbnails lost in the process. Then the tedious task of picking out the kernels began. You used a wire hairpin or a nut pick to dig the kernel out of its hiding place. The next time you go to the store and buy a little plastic package of black walnuts, remember what it cost someone to prepare them.

One of the joys of springtime was following after the plow. “Tasting” the feel of freshly-turned earth on bare feet! All winter you had worn high shoes that cramped your thoughts, if not your toes, but now for the first time since last fall, those toes could enjoy their freedom again.

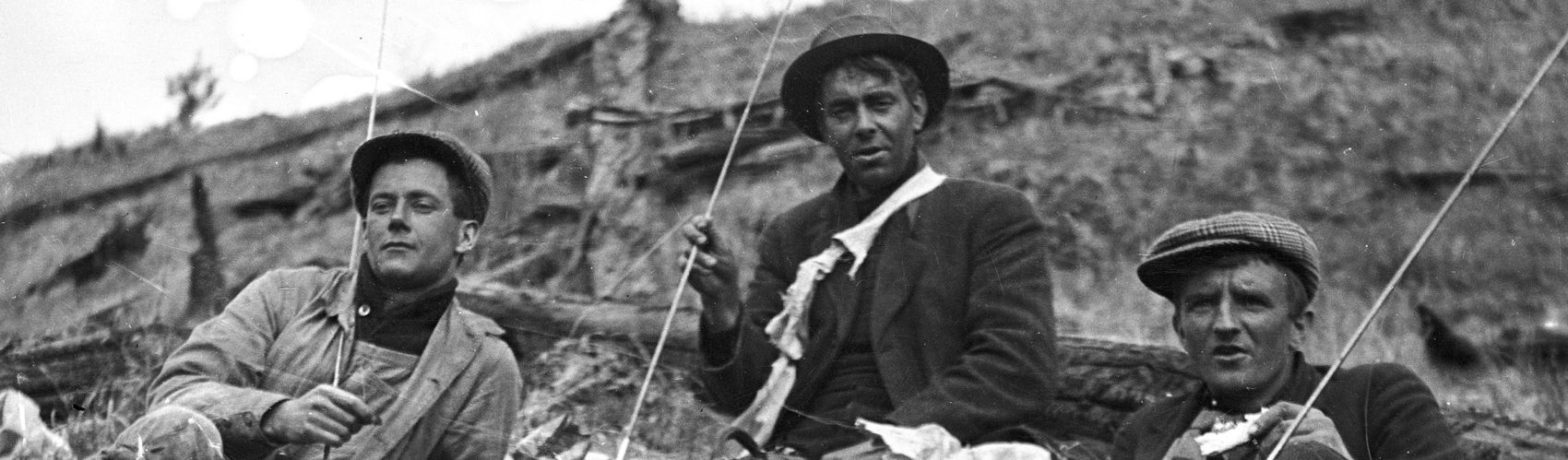

The earthworms that were plowed up must not be wasted, either. The fishing holes were beckoning. Many frying pans in the community would be full of tobacco box and black sunfish the next few days. (People call these fish bass today.) What a glorious way to spend a lazy afternoon–sitting on the river bank with a home-grown fishing pole in your hands and a string of three or four five-inch fish flapping around in the water beside you! Then is when your dreams of the future really blossomed, the fruit might never mature, but you had the pleasure of the blooms, anyway.

The words “hay harvest” bring varying responses. Some of them are happy; some are filled with dread and fear; some recall hard work and sweat, and there are many memories of pleasurable experiences. Children had certain pre-arranged jobs connected with harvesting. There was always the continuing job of carrying water from the spring to the workers. If they were working as much as a mile away from the house, dinner Must be carried to them–otherwise, it Must be served on the table. Someone had to ride the horses to haul the hay shocks to the stack area, and of course the small fry were selected for the job so that everyone big enough to “pitch” hay would be available for that job.

Two things were dreadful to me about those haying days. The sweat bees stung my legs as I rode bareback on the horse. I was so afraid of them that if one was flying around me, I was likely to forget to guide the horse to the right place. A few tears were inevitable because, if I got stung, I cried, and if I failed to guide the horse properly, I got scolded and I cried. And then I was always afraid I would see a snake. My brothers were older than I, and they assured me they would protect me, but there was always the idea that they might be far away.

Nell was a fine horse. She could travel well in a buggy, and she was a five-gaited traveler. My Dad was very proud of her, but she had one big fault–she was afraid of cars. On the rare occasions that we would meet a car on the road, she had to be held by the bridle and talked to, patted, and reassured. We were always sent scampering up the bank above the road for protection as soon as we heard a car approaching. (You could hear them a mile away in those days.)

Old Nell and I had a mutual understanding with which Dad could never agree. As soon as Nell saw me approaching with a bridle, she would lay back her ears, bare her teeth and run at me. I never went far from the fence and always made it over safely before she got there. Dad insisted she would not hurt me and he would send me back again and again. If my memory serves me right, I never did prove that she wouldn’t eat me up. One of the boys always ended up catching her and then I could ride her or lead her anywhere.

Country children were taught to be afraid of certain things. My list included: mad dogs, gypsies, snakes, buck sheep and bulls. In our wandering around the country, we avoided fields where there were sheep or cattle, so that was usually taken care of. But we couldn’t tell when a band of wandering gypsies might come through. (I remember seeing one band off three wagons when I was very small.) Any time we were on the road and heard a wagon coming, we visualized gypsies until it came into view and we knew the people.

A boy in our county, we didn’t know the family, had been bitten by a mad dog and died a terrible death. So this idea of fear would fill my thoughts if I chanced to be alone for any distance away from the house. I suppose I have run many miles fleeing from an imaginary dog. I never saw a mad dog until many years later, and then it wasn’t a strange dog, but our own.

Dad had a sister, Aunt Callie, her name was really Calfernia, who lived in the nicest house in all the Countryside for miles about. It was built on the top of a steep hill about three miles down the river from Berea, our little village. When the weather was good, you could drive there by buggy or wagon, or ride horseback. Most people walked over the hills and avoided crossing the river, which was necessary if you went by road.

To my childish mind, this great two-story white house was a castle in the clouds. It had a wide stairway with railing that was perfect for sliding, providing you didn’t get caught! If you did get caught, once in a long while, you were likely to stand up for a few hours in order not to add to the pain that was present with you.

The rooms were large and filled with interesting things which had not been made for children’s play toys. Two of the most interesting rooms were forbidden territory except on very infrequent occasions. The parlor was reserved for very special guests, which I never was in those days. Recently we have gone back there twice for a few hours, and that was the room we were taken into. I had to ask to see the kitchen and dining room. Cousin Julia is now dead and only her sisters, Conza and Draxie, and Rupert, their brother, still live there.

In 1965 when we visited there, after a bumpy and dangerous trip up the hill, we parked the car in the yard. Conza came out to warn us to be sure all windows were closed; otherwise, we might not have any upholstery left, for one of the horses was in the habit of eating all such delicate repasts. We didn’t know how smart the horse was, so we locked the doors, too.

There were special chairs covered with velvet and lovely soft cushions in every one. A table held an “Aladdin lamp,” which was a special oil-burning lamp that was much better than the ordinary ones used in the rest of the house. On the walls of this room hung the prize pictures of the members of the family. They were “enlarged” and framed in wide gold-colored frames about two by three feet, and some of them were larger. Those pictures are still there, and on the table stand is the same velvet-covered album of pictures that was their pride and joy a half-century ago.

Aunt Callie and Uncle John have been gone many years, and their children who still live there are now older and more feeble than I remember- my uncle and aunt. No wonder, for they have worn their lives out in that beautiful but inconvenient setting. Even in this modern day they must still carry nearly all their drinking and cooking water from a spring at the foot of the hill.. They have a drilled well on the back porch, but it never would supply more than a few buckets of water a day during the must ideal circumstances. When I was a child, I carried many buckets of water up that winding path. The girls of the family, Julia, Conza, and Draxie, made a large wooden yoke which they placed across their shoulders to aid them in this difficult task. A rope hung from each end of the yoke, with a hook on it, which they placed in the handle of the bucket; thus, the weight of the load they carried was distributed across their backs. I could never try it, for it didn’t fit me. Even as a child, I thought this made them look like “beasts of burden,” for it was much like the yoke they placed on the oxen when they hitched them up to work.

Washday was an event. The dirty clothes were carried to a level spot by the spring; a fire was built under the huge copper kettle which was filled with water. The clothes were placed in a tub with cold water and left to soak while the water heated. The other tub was filled with hot water, just hot enough to make the hands turn red but not blister, and then the washing began. Home-made lye soap was used and the clothes were rubbed, piece by-piece, on a washboard. The white clothes were then boiled in soap suds for about a half hour and then put through two tubs of water to get all the soap out. The wringing was all. done by hand, and those baskets of clothes were heavy when they were carried up the hill to hang them up to dry! In the winter, rain water or melted snow was used and the kitchen became the wash house.

The early spring was a wonderful time to visit at Aunt Callie’s house, for they made maple syrup. I suppose the month varied some, for the sap must be gathered just as it began to move in the trunk of those sugar maple trees. The days would be warm and sunshiny and the nights quite cool. A dozen or so sugar maples would be “tapped” and buckets hung under the spout they placed there. The sap would continue to drip for a week or so, and the buckets would have to be emptied twice a day. It tasted like lightly sweetened water to me. Now, as I remember it, I think it must have been somewhat like coconut juice from a freshly picked nut. (I don’t care for it, either.)

It took long hours of boiling this sap to bring it to the stage of maple syrup. I think one gallon of sap would make about one-half pint of syrup. It was used in baking, on the table, and best of all, it was made into candy. I would be given a small dish of the hot syrup to beat and mold into candy for myself. They sold many pounds each year, molded in little heart shapes. When it had been boiled down and molded, it was the color of light brown sugar, but the taste was wonderful. Nothing that we have today tastes as good as I remember that did.

There was another juice that was boiled down for syrup in those days, also. Sugar cane was grown by many of the farmers and then in the fall, when :it was at the perfect stage of ripeness, it was cut, ground, and the juice boiled for molasses. They would make molasses for the whole community at one time and place. Someone had a large vat, which must have held a hundred or so gallons. A large hole was dug in the ground and fire was kept burning (wood was the fuel, by the way) under the vat for several hours until the molasses had the proper consistency. It took two to feed the fire and stir the syrup. Long-handled wooden paddles were used to stir the molasses constantly so it would not burn. We children would be permitted to use our own little paddles to stir the top, with the end in view of licking the paddle. I never liked molasses, but I did enjoy pretending to “lick” along with the other youngsters.

All of this has been written in an effort to recapture some of the charm and homespun pleasures of the common people of the non-urban population of the early twentieth century. You don’t need to long for those good-ol-days; just take time to visit some of these same areas today and you will find the essential atmosphere has changed but little. There will be some electric lights and appliances, some telephones, passable roads all year round, and a car in the barn, but the people who are still there have retained their same philosophy and simple way of life. You will find last year’s Sears Roebuck catalog in the outhouse, nailed to the side of the wall, for your convenience. The biggest change would be that you would find no young people. Many houses are empty and going to swift ruin that used to ring with the impetuous laughter and joy of family life. The old folks died and youth moved away; for urban life beckoned them!

I guess this retrospective view has turned to be like a session on the psychiatrist’s couch. The question is: Will these recollections do me or anyone else any good?

I found it! Thanks