I will now go back to my childhood and record events which took place out of my school life. When I was about 8 years old, Father bought a farm across the river from Hise Davis (which is the farm where Ellsworth and Sarah lived for years). The first year we had it, they killed 22 copperhead snakes and 2 black snakes over six feet long, one of them nearly seven. Some snakes!

The spring we bought the farm Father traded for a small roan mare, which we kept for 12 years and raised 7 fine colts. One of these (Midge) I bought from Ellsworth the spring Jennie and I were married and kept her for 7 years. This was the first horse I owned.

I lived a rather strange life as a child, as I had no friends among the children of the neighborhood and played with no one except my brother Delvia and sister Cleo and Uncle Elisha’s children. Elva and Dow came down once or twice a year, and Delvia and I went there as often. This was all the friends we had till I was 15 years old, when we began to play with Buddy and Day Hoff, who lived a half mile below us. This is why it has always been hard for me to make friends. I will mention these friends later.

When I was about six years old, we had diphtheria in a very hard form, and it settled in a sore in my foot. It ate a hole larger than a quarter between my big toe and the one next to it. They could find nothing to help it until a man from Weston came to help Father in the tan shop. He said it was the germs of diphtheria settled there. He had known several cases in Weston, and they had to use diphtheria medicine. This soon cured it up, but there was a scar there larger than a quarter long after I was grown.

A Story of Wolves

I will digress now to tell a story as told to us three children about 70 years ago by Dorinda (I believe her name was). She was Uncle Zibba Davis’ wife. She was then about 65 years old, and she said this happened when she was about 8 years old. It had been a very long, cold winter and the snow had been very deep for weeks.

One Sabbath morning her father hitched the horses to the sled and went to church, leaving the children at home. Two or three were older than she. There was not supposed to be any danger, so the children were not afraid. About noon one of the children said he saw some big dogs out in the yard. When they looked out, they saw a half dozen, a dozen. and then hundreds of great, fierce brutes which the older children knew were wolves.

They had a large dog in the house. One of the wolves stuck his head through a window (which was made of greased paper). The dog sprang upon a bed which sat by the window, grabbed the wolf by the throat before it could get anything but its head inside, and held on until the blood ran down the wolf’s neck and it was still. Then the dog let loose, and the other wolves ate it up. In an hour or two they all disappeared.

When their folks came home, there was no sign of the wolves except that two or three acres of snow was cut all up with wolf tracks. No wolves were seen for years. The old people said that it had been such a hard winter that the wolves could find no food, so they had selected that spot to start their migration.

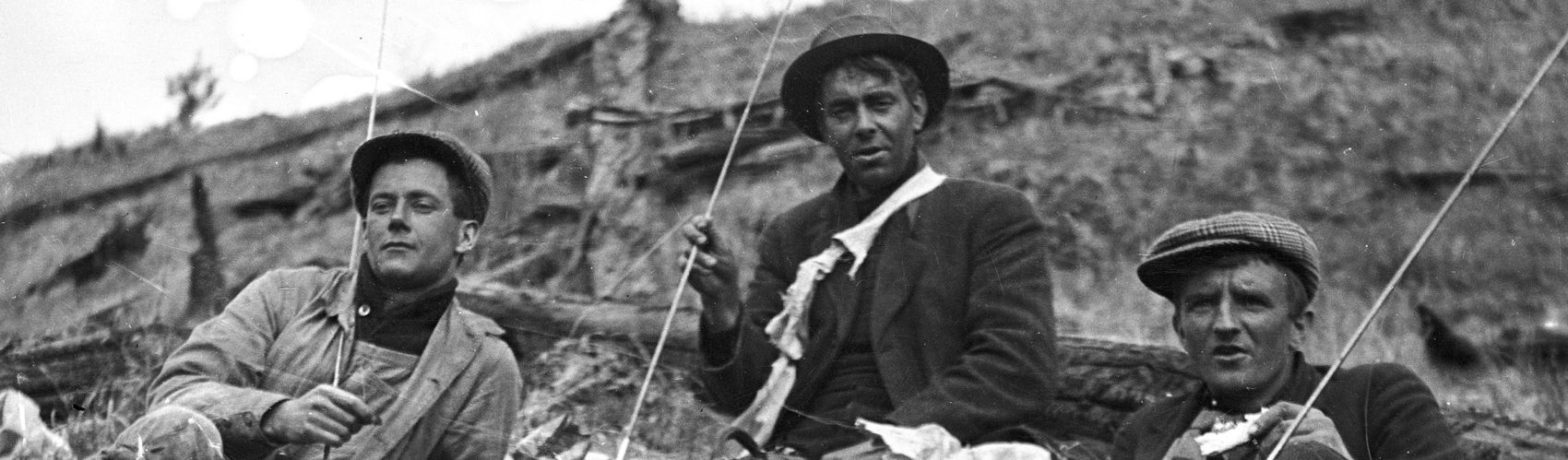

Hunting and Trapping

I remember my first hunting. Virgil and I were out together (I don’t know why) in the woods below the log cabin on the hill, when Virgil caught a rabbit under a rock. I remember how it squealed. I thought it was a ground hog. He gave it to me, and I sold it at Brake’s store. I was about six years old. This was the beginning of my hunting and trapping.

Hunting and Trapping with Delvia: By the time I was 10 years old, Delvia and I began to hunt and trap together. One day that winter we found a hole where we thought a skunk was denning, so we set a trap. The next morning when we went to the trap something was caught. It had dragged the trap the full length of the chain into the hole, so we could not see what we had caught. As everyone knows, you can have serious trouble with a skunk. To save my clothes I stripped naked and pulled the beggar out. It was a possum. Of course Delvia told what I did, and they laughed at me a great deal. But I got the possum!

We would take the dogs out and hole rabbits. Then we would set a box and catch them that night We could make a lot of money, for we could frequently catch two or three rabbits a month. We got from 5 cents to 10 cents apiece.

By the time I was 14, Delvia and I began to set snares for rabbits. We had fairly good success, and we lost no time as the traps were on our way to school. Once we caught a pheasant (which brought us 25 cents), and we felt rich. I remember one night it rained the fore part of the night and snowed the latter part. When Delvia got to the traps (I did not go that morning), he found two rabbits and a possum. We were rich again, as they were worth 50 cents.

I think I will give one more experience with snares and then drop that subject. The next winter for several mornings we found the snares thrown, the strings cut, and no game. I told Delvia we would get the sinner. So we fixed a solid framework, pulled down a strong pole and prepared for the kill. The next morning when we got in sight, the pole was up and there was a possum hanging by the neck more than two feet off the ground. In a week we had 5 or 6 possums; then we could go ahead catching rabbits. There had been a whole den of possums.

When I was 12, Delvia and I began to hunt at night and trap for skunks and possums. This was the fall that we hunted with John Meredith. We caught several possums, one of which was the largest I ever saw. John was a large, strong boy of 17, but he could only carry it a few hundred yards until he would have to stop and rest. He gave me half of what the pelts brought. He was one of my best friends for many years.

After this we hunted by ourselves for several years, as we had two good dogs. We caught many skunks and possums, which gave us much fun and a little money. This we used later to buy some sheep. Our two dogs were named Fisk and Bounce and were good hunters, day or night.

Night Hunting for Rabbits: One Sabbath Elva and Dow came down to stay all night. As this was in October and a good time to hunt, we decided to go; so we went and had no luck. Then at about ten o’clock, we decided to have a rabbit chase anyway and set them on a rabbit (they would not hunt rabbits unless we set them after them). They chased it down into a deep hollow, up a hill for over a half mile, and put it into a rail pile. We caught it and went back on the hill. They immediately started another, which they ran way down the hill for a long way before we got it also. As soon as we got to the top of the hill, they took another one down the hill and soon began to rave. So we hurried to them and found a hollow limb about five feet long in which the rabbit was hiding while the dogs ran from one end to the other and howled. Of course we got that one.

When we got to the top of the ridge, they started another one, which they soon put into a sink hole. It was now about eleven o’clock and getting rather cool, so we built a fire and began digging. In about a half hour we had the rascal. We felt it was quite a successful hunt as it is seldom you can hole a rabbit at night. We would often get two or three possums and sometimes a skunk in our night’s hunting (and sometimes nothing but tired legs). But we had lots of fun.

Mr. Mink, Muskrats and Coons: One cold morning in January, 1888, we saw where something had carried corn from the crib up the road across the river on the ice to a hole in the river bank. We set a trap and caught a muskrat, but its head was eaten off. We knew a mink was responsible, so we reset the trap. The next night we got Mr. Mink, which ended the threat to our muskrat trapping. This was our first mink, but we caught several after that.

We got 25 or 30 rats the rest of that winter, which we thought was quite good. But the next winter we really went after them with traps and barrels set along the bank (which we often visited before going to bed and again in the morning). We got as high as three rats in one barrel during one night. When spring came, we found we had sold 100 rat pelts that winter. This (with the other fur we caught-skunks and possums) made quite a showing as we got from 3 to 10 cents for our rat pelts.

We went ahead trapping, but not until after I was 18 did we get our first coon. There was a den near the school house where the steam would roll out. We decided there was something denning there. So we set a trap and caught a cub coon. Several years later I caught two fine big coons from the same den.

Sheep Enterprise: When I was about 15, Delvia and I took some of our money from furs and bought two sheep, which Father kept for the wool and we got the lambs. We would get from $2.50 to $3.00 for the lambs. When Father went North in 1892, we sold our sheep. We gained some knowledge of trading by buying and selling while we were boys. Father dealt with us as he did with other people.

Tenants

Jetts: The first tenant we had on the Davis farm was Alvin Jett, who was no good. One morning Father went over to the farm early. As he came back Mrs. Jett called to him and said, “Mr. Randolph, we don’t have a bite of bread stuff about the house.” (Jett was running around with the threshing machine getting good things to eat and doing nothing.) She looked as if she were hungry. Father said, “How about your potatoes. You had a nice patch of them.” She said that the potatoes were all gone, that they got along pretty well while they lasted, but it was hard to live without bread or potatoes. Father had Mother fix up a pail of flour and send Cleo and me up with it.

That afternoon Father went to see when the machine would be at our place. He took Jett out to one side and told him to go home and get his family something to eat, or starve with them, or he would cut him a hickory and give him a good whipping. Then he would throw his goods off the farm. For no man could run around and get plenty to eat and let his family starve on his farm. Jett toddled right off home.

Father often said that he hated “blamed orneriness.” (You may not know just what that word means, but in West Virginia to say a person is ornery is about as mean a thing as can be said of him.)

Now the next tenant was Dolph Weaver-but before I speak of him, I should tell one more story about Jett. He was with Marshall Meredith (who lived on an adjoining farm for 20 years and knew Father very well). Jett told him scandalous tales about Father. Some days later Marshall was at the mill when Jett came to the mill with a grist on one of Father’s horses. After he had tied the horse, Jett went to the mill. Marshall said to him, “How much does Asa charge you for a horse to go to mill?” Jett replied, “Not a cent. I can get a horse to go whenever I want it, and it doesn’t cost me a cent.” “It seems to me,” Marshall said, “if a man treated me like that, I wouldn’t talk about him like you did about Asa.” Jett replied, “I just talk that way about you when I am at your back.” So you see Marshall got it in the neck.

Dolph Weaver: This man, Weaver, was a big, strong young man who was married to a nice looking girl, but they preferred to fool around rather than work. In fact, they were both too lazy for any good use. Dolph told some of the neighbors that Father owed him a lot and wouldn’t pay him so he said he intended to whip him. When Father heard about it, he sent for Dolph to come down and settle up. They found on settling everything that Dolph owed Father between $10 and $15.

Dolph started off muttering to himself. Father let him go about 75 yards. Then he called, “Dolph, come back here.” When Dolph came back to the gate, Father said to him, “You have been telling it all around that you were going to whip me. John Snodgrass jumped onto an old man the other day and got an awful whipping. If you jump onto me, I’ll give you a worse licking than John Snodgrass got.” Dolph just went off without saying a word.

Frank Gardener: The next tenant was Frank Gardener, an Adventist from Kansas. Frank had two children (Charlie, about my age, and Minnie, a girl a little younger). Charlie was a playmate of ours while they were on the farm. Frank was a jolly, good-humored fellow who said he had moved over 30 times. So, you can see that he had the wander-lust.

He was a great hand to joke, and I never saw him get mad. I remember one day in harvest Ellsworth was raking hay when Frank said, “Ellsworth, you are a raker and a son of a raker.” Ellsworth said, “Frank, you are a rake and a son of a rake,” which tickled Frank. He only stayed one summer, when he took a notion to go somewhere else.

When I was teaching up in Taylor County, a man came to me on the bus and said, “Aren’t you Pressy Randolph?” I said, “Yes, but who the dickens are you?” “I am Charlie Gardener, and I am living in Clarksburg and working at Bridgeport.”

We met several times on the bus and talked over old times. He told me one morning that his father was living in Belington and was coming down to visit him soon. He thought they would be on the bus together some Monday morning. One morning I saw a gray-haired man who came up to me and proved to be Frank Gardener. He was just as jolly, good-humored as ever, and we had a nice talk. This was the last time I ever saw either of them.

John Meathrell: The next tenant was John Meathrell. He stayed three years and cleared out about four or five acres and raised crops on it, after which he bought where they now live and moved there. I might say right here that they [John and my sister Callie] were married when I was about ten years old, which was the first wedding I ever saw.

After this, Alva lived on the farm over a year. Then Ellsworth bached on it for a time before he married, after which he bought the farm, and they still own it.

More About the Tan Yard

I will now tell something more about the tan yard. Among my earliest jobs was grinding bark. Two of us children would hitch a horse to a bark mill, which was similar to a mill for grinding cane. There was a long whip hitched to a big log, on which were fastened metal teeth which revolved inside an iron rim with metal teeth. The bark was peeled from chestnut oak trees in the spring when the sap was up. When this bark was thoroughly dried, we would break it over the metal rim. It was ground between the two rims into fine pieces, which were used in tanning the leather.

We would sit there all day in very hot weather breaking the bark and keeping the horse going. Sometimes it took one all the time to keep that horse traveling.

There was a place under the mill where the ground bark dropped. When it filled up, it had to be hauled away. We children hated that work, but we did it just the same.

When the strength was taken out of the bark, we would skim out the worthless bark and scatter it over the ground about the vats. Sometimes the vats would be nearly full of water with bark on top and looked like the rest of the ground. When Delvy was about three years old, he came through the tan yard to a field beyond to tell us to come to dinner. When he got there, he was wet from his arms down. We found where he had walked into a vat. On the other side where he came out, water showed plainly where it had dripped from his clothes on the ground. I don’t think there were any of us children who failed to get into the vats at least once.

Many chickens and geese lost their dear little lives here. In fact a goose would only live a little while when she found she could not get out of the vat. Also, I lifted several pigs out of there. One blind horse which Emza rode from her school one time fell into one of the vats, but luckily got out.

The tan yard soon went to rack after Father left. I doubt if there could be a vat found now.

Working with Oxen

Before I was 16, I sold a horse for Father for $100 at Toll Gate. He had told me to take $80 for it if I could not get $100, but he never offered me any commission on it. This left us with but one horse, and Delvia and I began breaking oxen to work. We had two yoke at one time. Sometimes these oxen were quite wild and would run at the drop of a hat. One yoke would often get away with a sled and run through the woods or pasture until they ran afoul a tree or bush. Then we would go and back them up, get them around the tree, take them back to the road, jump on the sled, and away we would go.

We would often do our plowing with these oxen. In fact, we did all kinds of work. We would sometimes ride one ox we called Buck. But sometimes he would put his head down, snort, and we would land on the ground.

The winter I was 17, we cut a large lot of timber and had it sawed. One yoke of our oxen, which was white, helped in this work. We called them Lamb and Lion. They were very able cattle. I did not go to school this winter, but helped with the logging and stacking lumber.